Hello and welcome!

époque press is an independent publisher based between Brighton and Dublin established to promote and represent the very best in new literary talent.

Through a combination of our main publishing imprint and our online ezine we aim to bring inspirational and thought provoking work to a wider audience.

Our main imprint is seeking out new voices, authors who are producing high-quality literary fiction and who are looking for a partner to help realise their ambitions. Our commitment is to fully consider all submissions on literary merit alone and to provide a personal response.

Our ezine will showcase a combination of the written word, visual and aural art forms, bringing together artists working in different mediums to encourage and inspire new perspectives on specific themes.

For details of how to submit your work to us for consideration please follow the submissions guidelines and for all other enquiries please email info@epoquepress.com

Hello and welcome!

époque press is an independent publisher based between Brighton and Dublin established to promote and represent the very best in new literary talent.

Through a combination of our main publishing imprint and our online ezine we aim to bring inspirational and thought provoking work to a wider audience.

Our main imprint is seeking out new voices, authors who are producing high-quality literary fiction and who are looking for a partner to help realise their ambitions. Our commitment is to fully consider all submissions on literary merit alone and to provide a personal response.

Our ezine will showcase a combination of the written word, visual and aural art forms, bringing together artists working in different mediums to encourage and inspire new perspectives on specific themes.

For details of how to submit your work to us for consideration please follow the submissions guidelines and for all other enquiries please email info@epoquepress.com

époque press

pronounced: /epƏk/

definition: /time/era/period

époque press

pronounced: /epƏk/

definition: /time/era/period

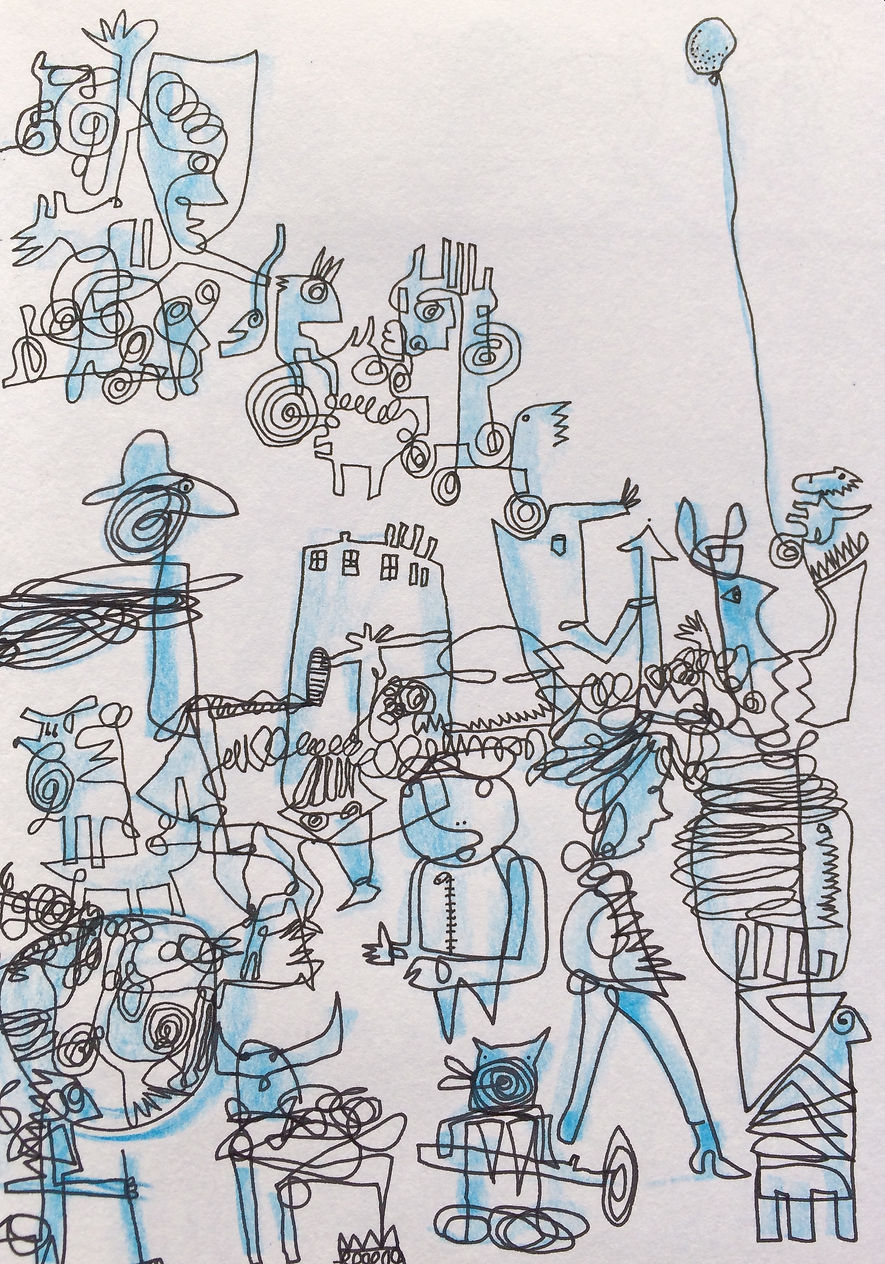

Alan McCormick lives with his family in Wicklow. He’s been writer in residence at Kingston University’s Writing School and for the charity, InterAct Stroke Support. His fiction has won prizes and been widely published, including Salt’s Best British Short Stories and Confingo. Alan also collaborates with the London based artist Jonny Voss. Their work has featured regularly on the web at 3:AM Magazine and Dead Drunk Dublin. Their book ‘Dogsbodies and Scumsters’ was long-listed for the 2012 Edge Hill Prize. Alan’s stories and his illustrated work with Jonny have appeared on previous Époque ezines.

See more at www.alanmccormickwriting.wordpress.com and www.jonnyvoss.com

Of their collaborative work together, Alan says…

‘About fifteen years ago Jonny started sending me sketches he made whilst walking around the pre Olympic canals and wastelands of Walthamstow and Hackney. I responded with short pieces of writing, nearly always with the first idea that came into my head. We called our collaboration Dumpsters (later morphing into Scumsters). See a small sample here http://www.deaddrunkdublin.com/stories/alan_mccormick/dumpsters/index.html.

We carried on working in this way, producing hundreds of pieces over the years, some of which were included in our book Dogsbodies and Scumsters. Sometimes Jonny also illustrated my writing, as he did with Cream Crackers for the Frenetic themed ezine by époque press, but for Affinity we went back to the beginning, and Jonny sent me a picture from his neighbourhood, which I responded to in words – affinity lying in the collaboration itself, our liking for spontaneity and immediacy, and in the way our minds can sometimes spark and combine to produce something that neither of us could produce alone. The Optimistic Recyclist is at it too, splicing together strange new life from the dead and barely living.’

THE OPTIMIST RECYCLIST

In the low tide scrub hinterland fringing the canals of East London, all manner of life is exhumed: carved out cats, whose missteps had fatally wrong footed them into a starving badger lair; an empty marmalade jar divested of its fairground retro goldfish prize (three consecutive hoops on a roadside cone); a deflated helium balloon crash-landed from a child’s party; a bird spectacularly entangled and carried away by a goal net unfastened in a gust of wind.

Under this moody sulphurous globe of late autumn, amongst all the death and detritus, a woman walks, head down, wringing her hands in a vain attempt to wipe away thoughts, her brain frazzled and beset by fear. She doesn’t notice a resurrected, reborn half-dog-half-cat holding a Dyson leaf collector in its reconstructed paws; nor the legless, one-claw-one-hand surgical philosopher with his chest clasped tight in fish gut. It’s a pity for his words are exemplary:

‘Do it to yourself, do it to others, patch up the armless and fill the poor souls with their stuffing taken out, put crows eyes on crows feet, jumpstart a de-frosting Iceland salmon and sew an aqualung through its spine, taxidermy the taxi driver who lost all recall of his knowledge, give him a dog’s memory for treats and plant a Satnav into his frontal lobe . . . ‘

As he speaks, his lone claw chops creative life shapes into the sky, whilst his hand reaches in his pocket for a long discarded Strawberry Quality Street. ‘I hate these,’ he thinks. ‘If only I had the power to summon new life, not just resurrect and re-shape the lifeless, I could bring forth a chocolate caramel, or a purple clad toffee brazil.’ He spits the strawberry cream out and the half-dog-half-cat hoovers it up.

‘Waste not want not,’ munches the half-dog-half-cat.

The surgical philosopher, who has been closely watching the rejected chocolate disappear into his splendid domestic creation, is suddenly struck by a big idea. ‘Pass me the leaf collector,’ he commands, ‘for I can fashion something from it that may have benefit for life-form as we know it, something for the greater wellbeing of our planet.’

His words take flight towards the angst-ridden woman, who had passed by only a moment before: ‘Madam, would you allow me to adapt the leaf blower into a strimmer and splice it directly into your brain? Not only might it help you shed unnecessarily negative thoughts but it might shape burdensome worries into manageable bite-sized chunks’.

The woman turns: ‘Are you insane: some kind of DIY Jesus with ideas above your station?’

‘You’re not ready,’ the surgical philosopher surmises. ‘It’s understandable, I feel your pain, your confused state. But when you are ready, you know where to find me.’

‘In the looney bin,’ she replies, and yet even as she say this, she finds her feet taking small steps forward, drawing her imperceptibly towards the surgical philosopher, to a life without worries, a life without hands or feet.